Born From Tragedy

In the 1970s the quiet community of Love Canal, Niagara Falls, NY, garnered national attention when chemical sludge began seeping up from the Earth. Kids came home with chemical burns after playing outside, basements flooded with noxious water, babies were born with birth defects and cancer rates soared1. As a result, residents started organizing, prompting officials to take a closer look at the town. New York State officials tested the soil in the surrounding area and found 82 different chemical compounds present2. Many of them were known carcinogens constituting what would become one of America’s most toxic wastelands.

Residents blamed the government for their plight and rightly so. From 1942-1950, before the land was developed, Hooker Electrochemical used the partially dug canal from which Love Canal gets its name to dump by-product waste associated with their production of rubber and explosives3. When they closed down in the early 50s, they buried 22,000 tons of toxic waste in the canal4.

Later, the city of Niagara Falls school board bought the land from Hooker for $1 and began building what would become the suburb of Love Canal5. Hooker company employees warned city officials that the land was unsafe for a residential area6. However, officials ignored their warnings, resulting in an environmental and human health tragedy that prompted the creation of the EPA’s Superfund program in the 1980s.

Photo Credit: Center for Environment, Health, and Justice

What is the Superfund Program?

The Superfund program began in 1980 with the passing of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA ) which set aside money and resources to address uncontrolled hazardous waste dumps7. The program’s intention is to protect residents and the environment from toxic chemicals. In 1983 they developed the National Priorities List (NPLs) which classifies the most dangerous and urgent clean-up sites8.

Procedure for Declaring a Site

The superfund assessment process starts when the EPA is notified of a potentially dangerous site. Next, it is entered into the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Information System (CERCLIS)9. Afterwards a Preliminary Assessment (PA) is carried out in which officials gather historical information on the site. If necessary, a PA is followed by a formal site inspection. During site inspections, soil and water samples are taken. Then, the site is categorized using the Hazardous Ranking System10. The EPA determines a score by evaluating the risk it poses based on categories such as groundwater migration, surface water migration, soil exposure, and air migration11.

Cleaning Up a Site

Cleaning up a Superfund site involves creating a plan of action laid out in a Record of Decision (ROD)12. The ROD discusses plans for the land post-cleanup, site history, community involvement and remedy for contaminants. The following phases include Remedial Action–where the bulk of clean-up occurs– and, eventually, construction in which physical clean-up of the site is completed13. After construction, the EPA continues to monitor the site until it is no longer deemed a threat and can be taken off the NPL. Subsequently, the EPA can work with local communities to repurpose the land.

Superfund and Climate Change

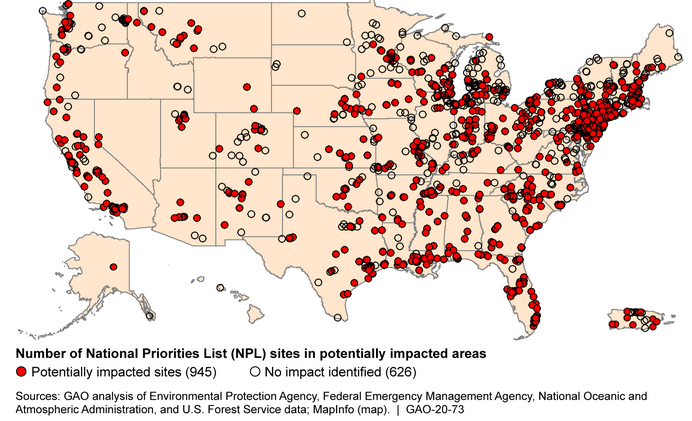

Photo Credit: Government Accountability Office

Though there are 1,700 NPLs across the country14, many residents remain unaware of these toxic wastelands in proximity to their homes and workplaces. Some sites are not marked by adequate signage so their existence flies under local radars. Awareness is important, especially as the topography of the country continues to transform due to ongoing climate change threats.

In 2019, the GOA published a report revealing that 60% of Superfund sites face damage caused by environmental disasters, like flooding and wildfires, that will be exacerbated by the climate crises15.

Additionally, Superfund sites pose a special risk for states burdened by increasingly unpredictable hurricanes. Widespread flooding caused by storm surge and sea level rise can leach chemicals from these hazardous sites into groundwater supplies and even into nearby resident’s homes. For instance, Hurricane Irma in 2017, and most recently Hurricane Ian, exacerbated these threats. With so many NPLs nationwide, a number of them coastal, securing these sites is vital to maintaining the safety of residents and the environment16.

The Homestead Airfield Site outside of Miami exemplifies this issue. Being the lowest lying of all the Florida sites, it takes only 12 inches of rain to flood the former airfield—an easy target during hurricane season17. Less than 3 miles away sits the Biscayne aquifer which provides drinking water to many in the region18. Thus, any contamination occurring at the Homestead site puts the quality of the Biscayne Aquifer water in peril.

Problems With the Program

Underfunding

While an important initiative, the Superfund Site program is not without its shortcomings. One often cited issue is the time it takes for the EPA to fully rehabilitate contaminated areas. For example, Pensacola’s Mount Dixon Site, located atop what used to be Escambia Wood Treatment facility, is still being cleaned up decades after the company closed down in the 1980s19. Part of the battle is the EPA’s struggle to secure funding which often leads to long stalls in the clean-up process. The agency’s budget is nearly half of what it was at its inception, leading to a reduced capacity to enforce regulations and initiate clean-ups at such toxic wastelands.20

Environmental Injustice

Sites that go ignored are overwhelmingly located in low-income and minority neighborhoods21. A 2015 study took a historical approach, analyzing siting of hazardous waste facilities from 1966 to 1995 and found that hazardous waste, treatment, and storage facilities were sited in neighborhoods undergoing white move-out and minority move-in22. As such, a legacy of environmental racism ensues. As of 2020, 1370 NPLs had yet to be cleaned up, with 50% of them located within a one to three mile radius of a minority community 23.

What Can Be Done?

- Elect local and national officials who emphasize environmental and public health

- Research the location and status of Superfund sites using the EPA’s database to stay up to date on toxic wastelands in your community

- Report potential hazardous waste sites to your state’s Department of Environmental Protection

Sources

- https://grist.org/justice/love-canal-the-toxic-suburb-that-helped-launch-the-modern-environmental-movement/

- https://grist.org/justice/love-canal-the-toxic-suburb-that-helped-launch-the-modern-environmental-movement/

- https://archive.epa.gov/epa/aboutepa/love-canal-tragedy.html

- https://archive.epa.gov/epa/aboutepa/love-canal-tragedy.html

- https://archive.epa.gov/epa/aboutepa/love-canal-tragedy.html

- https://grist.org/justice/love-canal-the-toxic-suburb-that-helped-launch-the-modern-environmental-movement/

- https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-history

- https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-history

- https://www7.nau.edu/itep/main/docs/waste/superfund/Sprfund_SiteAssessmentInfo_EPA.pdf

- https://www7.nau.edu/itep/main/docs/waste/superfund/Sprfund_SiteAssessmentInfo_EPA.pdf

- https://www7.nau.edu/itep/main/docs/waste/superfund/Sprfund_SiteAssessmentInfo_EPA.pdf

- https://www7.nau.edu/itep/main/docs/waste/superfund/Sprfund_SiteAssessmentInfo_EPA.pdf

- https://www.epa.gov/superfund/about-superfund-cleanup-process#rdra

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/superfund/

- https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-73

- https://www.enr.com/articles/50850-superfund-still-struggling-at-40

- https://www.ejatlas.org/conflict/homestead-temporary-shelter-for-unaccompanied-children

- https://www.ejatlas.org/conflict/homestead-temporary-shelter-for-unaccompanied-children

- https://floridaphoenix.com/2022/01/06/decades-later-epa-still-working-on-cleanup-of-floridas-mount-dioxin/

- https://thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/555145-the-terrible-environmental-costs-of-stagnant-epa-funding/

- https://thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/555145-the-terrible-environmental-costs-of-stagnant-epa-funding/

- https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/10/11/115008/meta

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-09/documents/webpopulationrsuperfundsites9.28.15.pdf