Toxic Lake Apopka

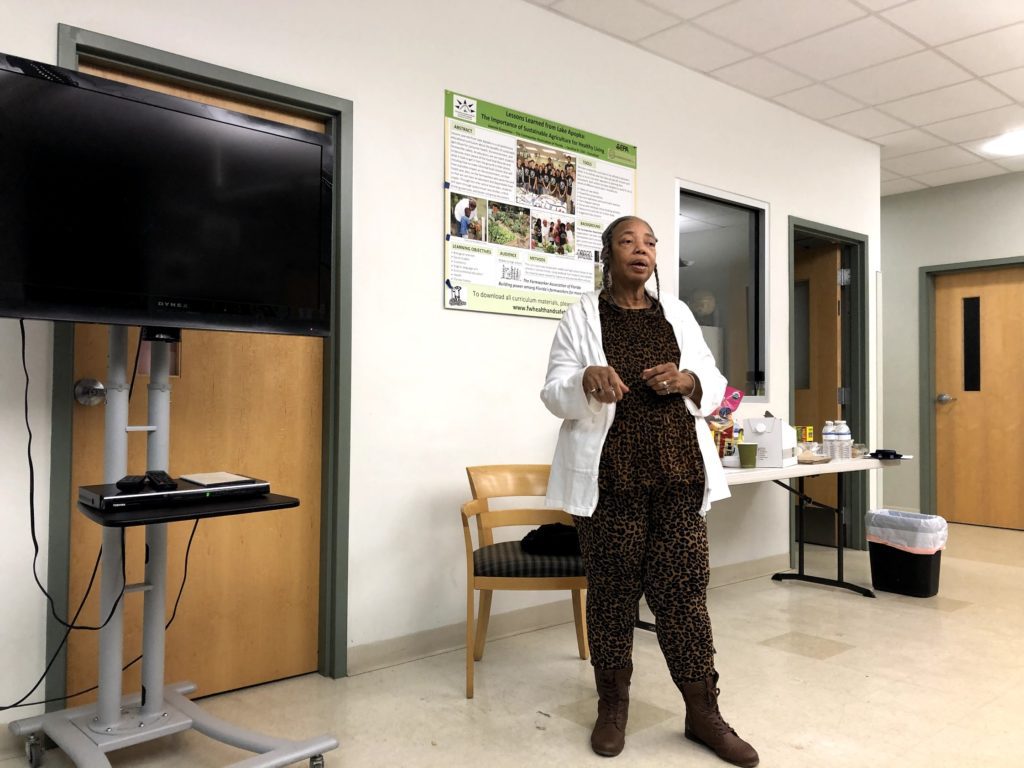

Toxic Lake Apopka. The History of agriculture here, and how we got to where we are. The Toxic Tour of Lake Apopka, led by Jeannie Economos of the Farmworker Association of Florida, conveys the deep history of Lake Apopka North Shore, agriculture and nutrient pollution. The synopsis below provides a snapshot of Central Florida’s systems of pollution and the beginning of a long road to environmental justice. We met with Economos again on Feb.1, for our second Toxic Tour. This is what we learned.

The history of agriculture and Lake Apopka

It all started in the 1940s, when the United States government was seeking land for agricultural purposes to assist in providing food to troops during World War II. The north shore of Lake Apopka, located in Central Florida, became the target, amounting to about 20,000 acres of the land converted for agricultural purposes. Farmers built pumps, dikes and levees to control the flooding and draining of this farmland. The shallow marsh would act as the “kidneys” of the lake, which connects to the Ocklawaha River and eventually the St.Johns River. North shore farmers would flood the fields in the summertime, to prevent soil oxidation, increase weed control and drain the land during fall, winter and spring to engage in agriculture. The result was a system of flooding and draining that amounted to tons of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, insecticides and other nutrient-rich substances flowing into the lake for over 50 years.

In the 50s and 60s, Lake Apopka was a huge tourist destination and a bass fishing mecca. Fish camps, hotels and local businesses supported an eco-tourism economy. Yet with the agricultural operations, the nutrient pollution led to full-scale algae blooms and eutrophication, the process by which a body of water becomes overridden with plant growth, usually due to land runoff, depleting oxygen levels and killing much of aquatic life. What was left was the “pea soup” water full of contaminants. The lake’s ecosystem eventually collapsed, and so went the eco-tourism industry with it.

The heat was on to try to save Lake Apopka. Dredging, constructing holding ponds and other activities were all proposed solutions, each having their own set of limiting factors. Some of the north shore farms tried to mitigate the problem as well. Duda Farms created a retention pond to hold the water, in an attempt to prevent phosphorus (a nutrient that can cause excessive plant growth) from being released into the lake. Zellwood Farms tried alum treatment, sending water into alum treatment plants to bind phosphorus before releasing it back into the lake, but this process didn’t work on dissolved phosphorus. The issue persisted for another 20 years, until someone with a radical revelation came along.

In the 1980s, a scientist from the University of Florida named Lou Guillette studied the comparison between Lake Woodruff and Lake Apopka alligator populations. What he found was unsettling: In Lake Apopka alligators had low rates of reproduction, due to males having high estrogen levels, and females high testosterone levels. Offspring exhibited reproductive-related malformations, birth defects and other distinctive issues that spoke to the severity of the pollution crisis.

Another discovery of Guillette’s was the operation of Tower Chemical Company, a chemical company that operated near the headwaters of Lake Apopka, and that mixed and distributed chemical pesticides like DDT. In 1979, there was a spill of pesticides into a holding pond that went into Lake Apopka. The investigation revealed that the exposure of these animals to organochlorine (the class associated with these pesticides) caused the reproductive problems with the alligators. His findings were ill-received at the time, but all over the United States similar studies were being conducted regarding DDT and ecosystems. Endocrine disruption was discovered as the scientific explanation for the reproductive issues in these animals, which alters organism’s hormone systems, causing cancer, birth defects and disorders. A scientific backing to Guillette’s argument gave him the credibility and support in the lake cleanup efforts—all while the public urged for lake beautification for outdoor activities and a regeneration of eco-tourism.

In the 1990s, after decades of lake cleanup attempts, the state of Florida passed the Lake Restoration Act. As a result, on May 31, 1998, many of the farms were shut down, in an effort to restore the lake back to its natural state. That fall season, the farmland was flooded.

Birds flocked to this area and fished in the shallow waters of the north shore. When Christmas came, the Audubon Society’s winter bird count came up devastatingly short. It was the worst bird death ever recorded in the United States. Thanks to two men from the US Fish and Wildlife Service, they found out that the culprit behind the loss in avian life was due to organochlorine pesticides.

Even though this class of pesticides was banned in the 60s and 70s, bird life on Lake Apopka was still under siege. Persistent organic pollutants take an extended period of time to break down and can bioaccumulate in organic organisms for decades. But birds, alligators and fish weren’t the only ones affected. If these toxins had such a devastating effect on wildlife, imagine what they did to humans.

Farmworkers and Lake Apopka

Thousands of farmworkers worked day after day to cultivate and harvest crops laden with chemical pesticides. Men, women and even children would experience direct contact with the pesticides on the fields. This created a huge health risk to this population of people. With so much public awareness given to the wildlife, soil, and water of Lake Apopka, low-income farmworkers, equally exposed to deadly pesticides, were not given the same attention. Jeannie Economos, pesticide safety and environmental health project coordinator for the Farmworker Association of Florida, hears stories of toxicity affecting these farmworkers every day. She says that “because the people on Lake Apopka were low-income farmworkers, mostly Haitian, African American and Hispanic, there has been no concerted effort to look at the health effects of these people.”

Since organochlorine pesticides bioaccumulate, they affect succeeding generations of these families. Illnesses from lupus to cancer have been found in the health history of many families of this area, which are archived as recorded interviews led by the Farmworker Association of Florida. Economos urges that a study focusing on the farmworkers who lived and worked in this area of Apopka could produce important information regarding the impacts of exposure to these chemicals, and how it affects their health over time.

Here’s how you can help

Donate to the Farmworker Association of Florida.

Donate to the Lake Apopka Farmworkers Historical Mural Project. It’s critical that the voices of the farmworkers who have had to endure exposure to harmful pesticides for the sake of industrial agriculture are not lost.

Volunteer or attend a Toxic Tour. Call (407) 886-5151 or email info@FloridaFarmworkers.org.

Join Farmworker Association of Florida for the Women2Women Conference on March 28. This conference is meant to bring together women of different cultures, races and ages in the community. It’s not too late to volunteer!

Call your representative in support of H.R.6631 (Ban Nerve Agents In Our Food Act of 2018) and H.R.3668 (Asuncion Valdivia Heat Illness and Fatality Prevention Act of 2019).

Sign the Heat Stress Protections Petition

Listen to our podcast, where Lee Perry, chief operations officer of IDEAS For Us, sits down with Jeannie Economos to discuss the complex issue of our industrial agriculture system.