Valerie Anderson, a geographical information science analyst, doesn’t have a favorite area of Split Oak Forest so much as a favorite time of year: fall. The season brings scores of purple flowers to the 1,700-acre nature preserve. Garberia, Vanillaleaf, Hairy Chaffhead, Slender Blazing Star. These are just a handful that capture her interest, not only for their resplendent colors—a mix of fuchsias, a mosaic of purples—but for their “glorious smell” and pollinator value. “You wouldn’t imagine that Florida creates all these different kinds of purples,” she said. “But we do—and they all bloom at the same time!”

Anderson, who is 31, is athletically built and wears a beaming smile when describing her favorite subject, endemic plant species. She led the way down a sandy trail near the entrance of Split Oak. The forest lies on the outskirts of Orlando’s Lake Nona community and sprawls into Osceola and Orange counties. Uniquely, it’s one of the few conservation areas in Florida that bans camping and hunting. Only hiking and permitted horseback riding are allowed.

As Anderson cataloged the different types of trees and grasses along the path, an air of calm enveloped the landscape, a beauty and stillness that felt undeniably transportive. The sun shone brilliant in the midafternoon overcast sky. Turkey oaks, with their fiery red leaves, stood majestic against a background of dense underbrush and vibrant green wiregrass. Canopies of Spanish moss soughed lightly in the breeze.

Split Oak Forest Wildlife and Environmental Area is named after a 200-year-old oak tree that split in half and survived. The forest is home to over 700 species. Furthermore, thirty of these are either endangered or threatened. This includes the gopher tortoise, Florida scrub jay and bald eagle. In the mid-1990s, Osceola and Orange counties purchased the conservation as a mitigation bank to protect the wetlands and wildlife there. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) now manages the property. They preserve the area by conducting prescribed burns, mechanical treatments and chemical removal of invasive species.

Split Oak also recently became FWC’s top preservation site for identifications. In 2018, the preserve had over 4,000 observations of living organisms, according to Florida Nature Trackers. Anderson, who plans to participate in her fourth bioblitz at Split Oak this spring, described a wetland there where she once discovered a rare plant that hadn’t been documented in the semi floodplain called Florida joint-tail grass. “It’s a super cool endangered grass, and it’s the only place where I found it on the property.” She paused, casting her gaze at an upland in the distance. “And now Central Florida Expressway Authority wants to put a road right through it.”

Building a road through conservation land that holds restrictive covenants—as Split Oak does through the Preservation 2000 Program, which protects it from developments in perpetuity—is as complicated a process as navigating a multilane highway during rush hour traffic. Orlando’s rapid population growth—expected to reach 5.2 million by 2030, according to a 2019 report—means more developments, more highways, more infrastructure, all of which pose a threat to conservation and wildlife habitats.

The argument is a familiar one. Staunch environmentalists want to preserve nature. Developers need acreage to make money. But the real issue, as the case with Split Oak demonstrates, isn’t about greed and the environment, about people and the natural resources they plunder or even about right and wrong. It’s about setting a precedent. If easements meant to protect natural habitats can be infringed upon, then what conservation areas, if any, are safe?

The vision of division

Osceola County Expressway Authority (OCX) was first to propose the idea of a 9-mile extension that would head east from Osceola County and south into Deseret Ranches, a sprawling 290,000-acre parcel that spans Osceola, Orange and Brevard counties. The new road would make way for a massive 24,000-acre community called Sunbridge, comprising thousands of residential units and over 9 million square feet of commercial space. Tavistock Development Co. and the corporate family of Deseret Ranches are the lead developers backing the $1 billion project.

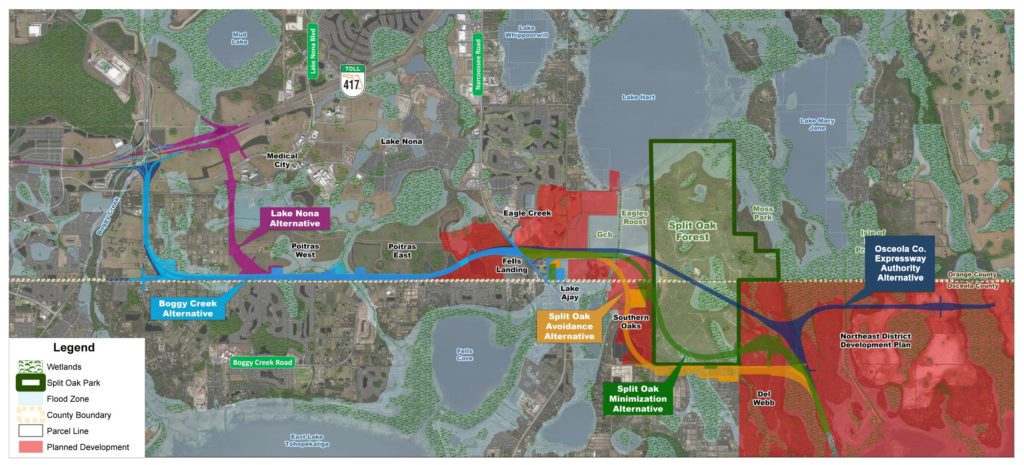

Talks of the Osceola Parkway Extension began in earnest around 2017, though the road had been in various planning stages for 15 years. OCX originally mapped out an alignment that would pass directly through Split Oak. Luckily, this idea did not come to fruition. But as Central Florida Expressway Authority (CFX) took over the project, absorbing OCX, new proposals for alternate routes surfaced.

One would avoid the park entirely but would also cut through suburban neighborhoods, necessitating an eminent domain and costing CFX an additional $100 million to develop. Another involved a road that would cut farther south but still intersect with Split Oak, though at a lesser severity—impacting a total of 160 acres. In exchange for approval of this route, Tavistock has offered 1,500 acres of nearby agricultural land to mitigate the damage of paving a highway through a historic nature preserve. Neither CFX nor Tavistock could be reached for comment.

While Charles Lee, director of advocacy at Audubon Florida, called the original plan “a horrible proposal.” He supports the new alignment. He added that if CFX were to choose the alternate route that circumvents Split Oak, new planned developments would encroach all but the southern boundary of the forest. This, he explained, would be detrimental to the future of Split Oak. It would create a “fence line” around wildlife corridors, fragmenting habitats and making prescribed burns more difficult.

According to Lee, the 1,500 acres of donated conservation land under CFX’s new proposal contains “uplands with better quality pine and scrub habitat that will ultimately improve long-term management.” Other tracts will require more funding for restoration but are nonetheless usable. “If you look at the facts,” he said, “the 160 acres is a small price to pay.”

“The way these protections are being dismantled so quickly and with so little public input is very troublesome. This could become Florida’s new reality.”

On the surface, getting 10 acres of additional conservation land in exchange for merely 1 acre seems a sweet deal. Some environmentalists say that even a modest incursion on ecological systems can cause irreparable harm. Likewise, this includes greater consequences still for Florida’s endangered species, populations of which are already dwindling.

For others, the threat of a toll road through the park goes much deeper. “The severity is not what happens to Split Oak or the specific ecosystems; it’s that we don’t have any other way in Florida to protect conservations from roads and development,” said Anderson, who recently made a YouTube video explaining how the 1,500-acre mitigation land is mostly swamp, unable to be developed. “The way these protections are being dismantled so quickly and with so little public input is very troublesome,” she said. “This could become Florida’s new reality.”

Anderson has been hiking at Split Oak since 2010. As a graduate student at the University of Southern California, she wrote her thesis on the park’s historical ecology. For this, she won third prize in her class. Two years after graduation, in 2017, she came across a notice in Osceola News-Gazette for a public meeting. On the agenda was a plan to extend Osceola Parkway into Orange County. “It didn’t even have Split Oak on the map, just a fat corridor of where the road would go,” she said.

Her girlfriend told her that transportation officials were likely planning to bisect Split Oak. Anderson didn’t believe it. “I read all the conservation easements. … Split Oak was supposed to be safe forever,” she said. “And now it’s not because people in power can beat their chest and assume they can get things done on a local level.”

Anderson knew she had to fight back. If not her, then who would, she thought. In January 2017, she started Friends of Split Oak Forest, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to protesting the parkway expansion. From the outset, Anderson has spread awareness about the environmental costs of building a road through a nature preserve: the destruction to natural habitats, the loss of controlled forest burns, the public health risks to those living near highway construction.

Still, the project persisted. After a series of board meetings in December, at which CFX, Osceola County and Orange County approved the preferred alignment, preservation groups and Friends of Split Oak Forest anticipated a huge setback. Though CFX would still need approval from Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) and Florida Communities Trust. The FWC is the agency tasked with reviewing CFX’s alternate route and the road through Split Oak appeared a likely possibility.

Partly what sparked December’s approval blitz boils down to a misrepresentation of facts. At Orange County’s board of commissioners meeting on Dec. 17, CFX proposed its plan under a linear facilities administrative code. The code that should have been presented instead, or at least in addition to a linear facilities, as a request for land exchanges. Indeed, this code has far more restrictions and is more difficult to pass. Notably, the code requires, in part, a proposed exchange parcel of equal or greater value “in terms of upland acreage”; a “significant and clear net environmental, conservation and/or recreational benefit to the Project Site”; and “an affirmative vote [from a governing body] of at least three-fourths of its members.”

While some would argue the quality of the mitigation land, the result of the Dec. 17 meeting is clear: Commissioners approved the preferred alignment with a 5-to-2 vote, or 71% of the majority. Now, this means that CFX was just shy of the 75% of votes needed to pass its proposal.

This subterfuge felt particularly unsettling to District 5 Orange County Commissioner Emily Bonilla, who called the mitigation deal between CFX and Tavistock a “quid pro quo.” As she put it, “For Tavistock to go to CFX and say, ‘We need this toll road, and if you set this whole thing up for us, then we’ll give you this land’ is just wrong.” She went on, “I read both administrative codes, and the way I interpreted it is if you’re doing both, then you have to follow both—you can’t choose.”

The fight continues

On Feb.1 opponents of the Osceola Parkway Extension received a flicker of hope: Bonilla asked her fellow Board of County Commissioners to rescind the vote from the Dec. 17 meeting citing CFX’s misleading proposal. Significantly, Bonilla’s request raised no objections, and the mayor agreed the motion would be heard at the next commissioners meeting on Feb. 11. Additonally, Florida Communities Trust also made clear, according to Bonilla, that the board should review the parkway proposal under both administrative codes—including the request for land exchanges.

Meanwhile, when asked who suffers the most from a road through Split Oak—the surrounding communities? the environment? the animals?—Bonilla replied, “future generations.” She explained: “When I was little, I was told that I would never see a bald eagle. Do you know how that affected me as a kid? I thought, Wow, here’s this thing that I’ll never get to see, and it’s so amazing and majestic and beautiful, and I’m going to grow up and it’s going to be gone, thanks to these dumb adults.” Like the bald eagle, the gopher tortoise is another endangered species that calls Split Oak home.

“Split Oak is supposed to be a sanctuary for gopher tortoises,” Bonilla said. Now, a road could potentially plow through that sanctuary. She fears that someday she may have to tell her children that they will never see a gopher tortoise in its natural habitat. “Future generations deserve to see the majestic beauty that’s on this Earth,” she said. “They deserve that, and we shouldn’t take that away from them.”

Back at Split Oak, Anderson spotted a band-winged grasshopper on the ground, its verdant color standing in stark contrast to the white sand. Creating an enclosure with her hands, she coaxed it toward her. It jumped into the palm of her left hand and gingerly made its way up her forearm. Anderson held up her arm and giggled, the way a kid giggles after capturing a lightning bug for the first time. She then walked farther up the trail, the grasshopper clinging to her. As if, somehow, it knew she would be the one to protect it.

Something must be done. But what?

Action items to save Split Oak

- Friends of Split Oak Forest and League of Women Voters plan to take the case to Florida Supreme Court, if necessary. They need protesters at community meetings. Show your support at the Orange County Board of County Commissioners meeting Feb. 11. For more information or how to contribute, email Valerie Anderson at valerie@friendsofsplitoak.org.

- Then pressure Orange County commissioners with phone calls and emails in advance of the next board meeting on Feb.11.

- Next, sign this petition, created by Valerie Anderson, that opposes an expressway through Split Oak.

- Share this short documentary by Vince Marcucci and our podcast interview with Valerie Anderson on your social media platforms.

- Finally, join Friends of Split Oak Forest’s Facebook page for additional updates and upcoming events.

Sources:

https://myfwc.com/recreation/lead/split-oak-forest/

https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/florida-wma-split-oak-forest-wildlife-and-environmental-area

http://www.oppaga.state.fl.us/MonitorDocs/Reports/pdf/9678rpt.pdf

https://www.deseretranches.com/Home/Welcome

https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/os-cfx-split-oak-20180308-story.html

https://www.mcall.com/os-cfx-split-oak-20180308-story.html

https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/os-central-florida-toll-road-empire-20171214-story.html

https://www.flrules.org/gateway/ruleno.asp?id=62-818.015