Deep Sea Mining

Deep sea mining. Is it an environmental resource or a disaster? The practice has become a controversial topic in recent years. Some believe it is a great alternative to terrestrial mining, which is now on the decline. Others say the damage could outweigh the good.

Scouring the Deep: What is DSM and Why the Interest?

An image of polymetallic nodules. Photo from the Metals Company 2019

DSM is the process of retrieving mineral deposits from the deep- the area of the ocean below 200m that covers about 65% of the earth’s surface.1

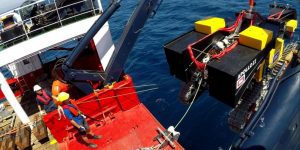

Photo of Apollo II being deployed during the first field trial in 2018. Image by Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research.

The process involves mining for polymetallic nodules, also called manganese nodules. These nodules contain manganese, iron oxides, and other metals that occupy all oceans but are generally found in areas where sediment collection is slow.2

Over the years, terrestrial deposits have been depleting. These deposits hold metals:copper, nickel, aluminum, manganese, zinc, lithium, and cobalt.1There has been a rising demand for these metals to produce high technology such as smartphones and green technology (solar panels and wind turbines).1

How Does DSM Work?

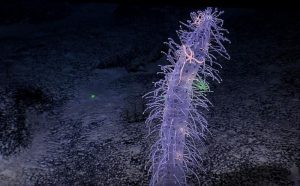

A submersible approaching a hydrothermal vent. Photo from National Ocean Service.

Miners use large, robotic machines to extract the ocean floor in ways similar to strip-mining on land.3 Whatever materials are found are pumped to a ship. The waste and debris from this extraction are dumped into the ocean.3

The Pros of Extraction

Image of submersible digging for polymetallic nodules. Photo by Earth Journalism Network

There are many supporters of the supposed benefits of this practice. The World Economic Forum report in 2014, estimated that the gold found in polymetallic nodules in seabeds is worth at least $150 trillion dollars.4

It is believed that the metals found in the deep can cut the costs of renewable technology. It is said that there is enough cobalt and nickel in the ocean to power 4.8 billion electric vehicles .5

Gregory Stone, chief ocean scientist at DeepGreen, believes “the disruption to the planetary system will be a lot less.”6 He also says deadly health impacts and child labor violations, both associated with DSM, can be decreased.6

The Cons of Extraction

Despite these possible benefits, there are still others who are weary of giving the practice a chance, and with good reason.

A deep sea sponge living on a Pacific Seamount targeted by mining contractors. Image by Zhang Jiansong/Xinhua/Alamy

Polymetallic nodules provide critical habitats for largely understudied species such as varieties of coral, sponges, urchins, squid, and shrimp.7 These species and habitats are slow growing and many of them are endemic- they don’t occur anywhere else on earth.1 If damage is done to them, a full recovery after mining could take thousands of years and that is if a recovery is possible.

Mining waste could introduce toxic material into food chains.7 These toxins could travel through the oceans and damage seamounts and coral reefs.7

It is also feared that DSM could cause light and noise pollution. DSM could disrupt species attuned to living in the dark and could change swimming and schooling behavior.7

What Happened in Papua New Guinea?

Jonathan Mesulam and his son campaigning to ban deep-sea mining in PNG. Image by Jonathan Mesulam / MiningWatch Canada.

DSM was first attempted in 2007 in Papua New Guinea. A submersible was used with a large drill, 5,250 feet below, near hydrothermal vents.7

By 2019, Nautilus Minerals, INC, the mining company, went bankrupt before retrieving any material.7 Papua New Guinea is now millions of dollars in debt.

Jonathan Mesulam, a resident, said his community experienced a serious impact. He states, “We were worried because the mining is experimental, there are no examples anywhere in the world, and Papua New Guinea has no regulatory framework.”7

He also said it affected their shark calling culture. Sharks are a major food source for the residents in Papua New Guinea and when the mining started the sharks left the waters.7

Who Can Prospect the Sea?

As a result of the possible risks of the aforementioned practice, mining regulations have been put in place in order to make sure that deep sea mining does not become a bigger issue. The exploration of seabed minerals can only be carried out under contract with the International Seabed Authority.8

Twenty-eight contracts have been approved in the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans.8This covers more than 1.3 million square kilometers of the ocean floor.8 Contracts have also been granted to small developing states such as Cook Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, Singapore, and Tonga.8

Alleviation Strategies

It is imperative to have a better understanding of the deep in order to lessen the damage to the habitats and marine life that can be caused by deep sea mining.

Excavation Baseline Studies

Baseline studies are used to understand what species live in the deep.1 This analysis helps scientists to understand how these species live and how mining could affect them.1

Excavation Environmental Impact Assessments

These assessments are needed to assess the full range of environmental damage from deep sea mining.1 It also measures the extent and duration of this damage.1

Digging Mitigation

Mitigation strategies involve establishing protected area networks to keep large areas of seabed undisturbed and can also involve improving mining equipment.1

Deep Sea Extraction and the Circular Economy

Circular economy is encouraging the repair and reuse of products to reduce the demand for raw materials from the deep sea.1

These strategies are the different ways scientists and conservationists are trying to minimize the effects of deep sea mining but it still seems too little is known about the deep for the practice to become a resource everyone can get behind.

Deep Sea Mining Sources

- “Deep-Sea Mining.” IUCN, iucn.org/resources/issues-briefs/deep-sea-mining

- Cronan, David S. “Manganese Nodule.” Science Direct, sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/manganese-nodule

- “Deep-Sea Mining.” Center for Biological Diversity, biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/deep-sea_mining/

- “Deep-Sea Mining FAQ.” Center for Biological Diversity, biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/deep-sea_mining/pdfs/Deep-seaMiningFAQ.pdf

- Baker, Aryn. “A Climate Solution Lies Deep Under the Ocean- But Accessing it Could Have Huge Environmental Costs.” Time, 7 September 2021, time.com/6094560/deep-sea-mining-environmental-costs-benefits/

- Ackerman, Daniel. “Deep-Sea Mining: How to Balance Need for Metals with Ecological Impacts, Scientific American, 31 August 2020, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/deep-sea-mining-how-to-balance-need-for-metals-with-ecological-impacts1/

- Alberts, Elizabeth Claire. “Deep-Sea Mining: An Environmental solution or impending catastrophe?” MongaBay, https://news.mongabay.com/2020/06/deep-sea-mining-an-environmental-solution-or-impending-catastrophe/

- Lodge,Michael. “The International Seabed Authority and Deep Seabed Mining.” UN Chronicle, The International Seabed Authority and Deep Seabed Mining