Drilling in ANWR

Drilling in ANWR…let’s talk about it. President Biden suspended drilling leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) earlier this month.1 Here’s why drilling should be avoided.

PHOTO FROM UNSPLASH/JORIS BEUGELS

Background

ANWR, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, is about 19.3 million acres today2 and is estimated by the U.S. Geological Survey to have between 4.3 billion and 11.8 billion barrels of “technically recoverable” oil.3 ANILCA, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, added 9.1 million acres to the original refuge in the 1980s, but added a provision to exclude potential developmental areas from federal protection.4 Section 1002 “prohibited leasing, development, and production of oil and gas in the refuge unless authorized by Congress.”4 The refuge’s 1.5 million-acre Coastal Plain was to be inspected for its oil and gas potential by Section 1002.4 The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act opened up the 1002 area of the Coastal Plain to leasing sales.5

The ANWR tract lease sales did not do as well as what was claimed by the Trump Administration. The previous administration claimed that the lease sales would make $900 million, but the January lease auctions only made $14 million over 11 tracts equalling about 600,000 acres.6 The major oil companies were not interested and there were only “three bidders — one of which was the state of Alaska itself”7 as $4.4 million3 of the sales came from Alaska’s state-owned economic development corporation, the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority.7 Five months later, the Biden Administration has “suspended oil drilling leases.”1

Environmental Impacts

Looking at the Past: Orcas, Seabirds, Salmon, and More

The oil industry has a history of badly estimating environmental effects and impacts of oil development and oil spills. For example, the Prudhoe Bay complex* covered 9,000 acres but its actual physical coverage “spread out like a spiderweb”4 across more than 800 miles through infiltration and drainage. The Exxon Valdez oil spill* released 11 million gallons of oil into Prince William Sound, Alaska4 and the first attempts at spill containment failed, so the oil slick spread out and covered 1,300 miles of coastline.8 More than two decades later, the Exxon Valdez spill is still having ecological effects.

14 of the 36 killer whales (orcas) in the Prince William Sound’s resident pod disappeared soon after the spill, their “lungs were seared by the toxic fumes.”9 The remaining members of the pod are victims of bioaccumulation*. They ingest mostly fish rather than sea mammals like Prince William Sound’s non-resident pod since the chemicals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are more heavily accumulated in the marine mammals higher on the food chain.9

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are toxic -they don’t evaporate from the shore after oil spills and cause long-term reproductive damage to the birds, fish, and mammals in the spill’s area.10 Eating these bigger mammals is harmful to the non-resident pod and the Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council researchers have concluded that there is “no hope of recovery.”9

“Estimates of the total amount of oil that remains in the environment have varied, but the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council, a government-created monitor, concluded that the oil disappears at less than 4 percent per year. At that rate, the council said, the oil will “take decades and possibly centuries to disappear entirely.”9

The Herring population has not sprung back to the original population which has reduced the small fish-eating seabird population, like waterfowl.9 It is thought that up to 300,000 of the original one million “seabirds in Prince William Sound died initially.”9 The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council found that 17 of 27 monitored species in Prince William Sound have not recovered. When Exxon hired people to wash the spilled oil off the shore, the high-pressure hoses “destroyed interlocking layers of gravel and flushed away fine sediments.”9 Those layers protected the beaches plus clams and mussels from storms. The damage to the shellfish had, in turn, slowed down the recovery of otters who feed on the mollusks.9 Even wild pink salmon did not reach its origin numbers almost 20 years after the spill. Before the spill, in 1984, Prince William Sound had 23.5 million pink salmon and in 2007 there were 11.6 million.9 Oil spills have the potential of damaging an ecosystem for decades.

*The Prudhoe Bay oil field is one of the biggest in the US and is located on the North Slope, Alaska.11 “The Prudhoe Bay oil fields and the Trans-Alaska Pipeline system cause about 500 oil and toxic chemical spills annually on the North Slope”12 and in 2006 Prudhoe Bay had its biggest spill which they were ordered to pay a $25 million dollar settlement in 2011 for the 200,000 gallons of crude oil spilled.13

*The 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill happened in the waters off the coast of Cordova and Valdez9 when the oil tanker, Exxon Valdez, crashed into Bligh Reef and tore open the ship’s hull -due to the captain drinking and leaving an unlicensed third mate to steer.8

*Bioaccumulation is “the accumulation over time of a substance and especially a contaminant (such as a pesticide or heavy metal) in a living organism.”14

ANWR “is home to polar, grizzly, and black bears, over 200 species of birds, 8 marine mammal species, hundreds of thousands of caribou, wolves, muskoxen, moose, and more.”15

Polar Bears

PHOTO FROM UNSPLASH/HANS-JURGEN MAGER

Environmentalists are concerned that drilling and oil exploration in ANWR’s Coastal Plain (or the 1002 area) will disturb the 2,000 polar bears between northwestern Alaska and the Canadian Northwest Territories.4 Pregnant polar bears use the Coastal Plain for denning during the winter; with the Beaufort Sea polar bears already having an equal birth rate and death rate, and drilling would increase the mortality of female polar bears.4 Biologists worry if the population could even endure any increased female mortality as they are “listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act,”16 especially when considering that female polar bears “abandon their dens when disturbed.”17

Only about 900 Southern Beaufort Sea polar bears remain today, that’s half of what the subpopulation was in the mid-1980s.16 With climate change and the thinning of Alaskan offshore ice, polar bears have been moving their dens onshore, “into or nearer the Refuge.”17

Caribou

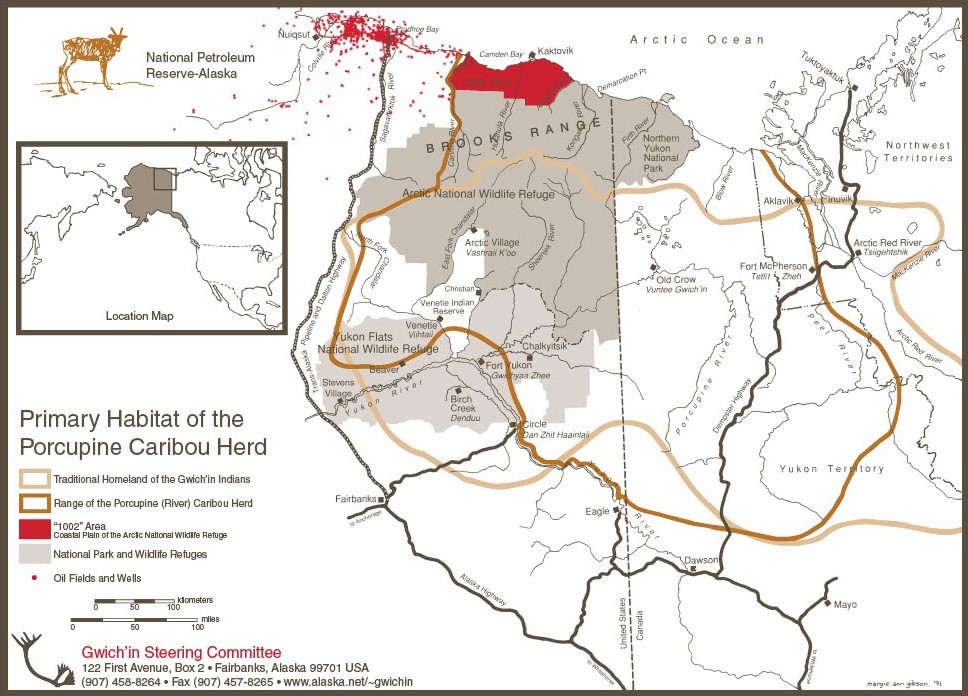

Drilling in ANWR would disrupt caribou migration patterns. The North Slope’s oil field activity disturbed the feeding habits of Central Arctic herd caribou, resulting “in reduced summer weight gain, decreased pregnancy rates, and increased mortality.”4 The Coastal Plain’s Porcupine caribou herd (the second largest herd in Alaska) has been predicted to have similar effects with drilling and development as the Central Arctic herd.4 The Porcupine caribou herd uses the Coastal Plain as a safe calving ground and the windiness of the area protects them from insects.

The Gwich’in Eskimos

The Gwich’in Eskimos, called the Caribou People, depend upon the Caribou for their food, clothing, tools, as well as a “source of respect and spiritual guidance”18 and their communities have about 200,000 caribou migrating through annually.19 The 15 Gwich’in settlements along the migratory route of the herd contain about 7,000 people who depend on Caribou for survival.20

Permafrost

Caribou also play a part in keeping permafrost from melting. ANWR is an Arctic desert and its subsoil is permafrost which remains frozen year around.4 In the summer, the top 30 to 100 cm (approximately 12 to 40 inches) of the ground thaws and then refreezes in the winter.21 There is a 900 to 2,000-foot-thick carbon deposit, made of dead organic material, below the surface in permafrost.22 The upper ten feet of the permafrost contains “10 to 20 pounds of carbon per square foot.”22 Warmer temperatures allow microorganisms to decompose the organic material in the permafrost and release greenhouse gases.23

“Soils in the permafrost region hold twice as much carbon as the atmosphere does — almost 1,600 billion tonnes.” 23

Caribou grazing keeps any tall plants from growing; plants taller than the snowpack allow the tundra to absorb more heat from the sun than reflecting it, which would cause earlier snowmelt and permafrost thawing.22 Drilling in the 1002 Area would disrupt their migration patterns, feeding habits, even cause them to abandon the area.

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, ANWR, should be protected and drilling should be avoided.

Sign the letter to permanently protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge-Coastal Plain, the Porcupine Caribou Herd and the Gwich’in Way of life: https://ourarcticrefuge.org/take-action/

Donate to Gwich’in Steering Committee: https://www.patagonia.com/actionworks/grantees/gwichin-steering-committee/donate/

Sign the letter to legislatively restore protections for the Arctic Refuge: https://secure.everyaction.com/OXibf-xw0UOE47pCr7dKTA2?MS=pata

Sign the letter to support the Arctic Refuge Protection Act: https://secure.everyaction.com/zE68GMOqXEurAvsgA7Hr3A2

Want to Learn More?

Watch the film Oil on Ice and check out the site: http://oilonice.org/

Read more on the re-introduction of legislation to protect ANWR https://huffman.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/rep-huffman-and-senator-markey-re-introduce-bicameral-legislation-to-protect-the-arctic-national-wildlife-refuge

Sources

- Davenport, Coral, et al. “Biden Suspends Drilling Leases in Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 1 June 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/06/01/climate/biden-drilling-arctic-national-wildlife-refuge.html

- “Programs: Oil and Gas: Alaska: Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.” Bureau of Land Management, www.blm.gov/programs/energy-and-minerals/oil-and-gas/about/alaska/coastal-plain-arctic-national-wildlife-refuge.

- Bourne, Joel K. “The Arctic Refuge Is Opening for Oil Drilling. Why Is Industry Interest so Weak?” Environment, National Geographic, 3 May 2021, www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/wilderness-crown-jewel-opening-for-drilling-industry-interest-weak.

- “Chapter Six: Oil Verses Wilderness In The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge .” The Environmental Case: Translating Values Into Policy, by Judith A. Layzer and Sara R. Rinfret, SAGE, 2020, pp. 177–184.

- “Secretary Bernhardt Signs Decision to Implement the Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program in Alaska.” U.S. Department of the Interior, 17 Aug. 2020, www.doi.gov/pressreleases/secretary-bernhardt-signs-decision-implement-coastal-plain-oil-and-gas-leasing-program#:~:text=The%20Tax%20Cuts%20and%20Jobs%20Act%20of%202017%20directs%20the,Gas%20Program%20area%20of%20ANWR.

- Aridi, Rasha. “The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Will Not Face Mass Oil Drilling-for Now.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 8 Jan. 2021, www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/arctic-national-wildlife-refuge-not-face-mass-oil-drilling-180976708/#:~:text=Keeping%20you%20current-,The%20Arctic%20National%20Wildlife%20Refuge%20Will,Mass%20Oil%20Drilling%E2%80%94for%20Now.

- Herz, Nathaniel, and Tegan Hanlon. “Arctic Refuge Lease Sale Goes Bust, as Major Oil Companies Skip Out.” Alaska Public Media, 14 Jan. 2021, www.alaskapublic.org/2021/01/06/long-awaited-arctic-refuge-oil-lease-sale-attracts-little-interest/.

- “Exxon Valdez Oil Spill.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 9 Mar. 2018, www.history.com/topics/1980s/exxon-valdez-oil-spill.

- Struck, Doug . “Twenty Years Later, Impacts of the Exxon Valdez Linger.” Yale E360, 2009, https://e360.yale.edu/features/twenty_years_later_impacts__of_the_exxon_valdez_linger.

- “Oil on Ice.”, directed by Dale Djerassi, and Bo Boudart. , produced by Dale Djerassi, et al. , The Video Project, 2005. Alexander Street, https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/oil-on-ice.

- “Prudhoe Bay Oil and Gas Field, North Slope, Alaska, USA.” NS Energy, www.nsenergybusiness.com/projects/prudhoe-bay-oil-field/.

- Williams, Jamie. “7 Ugly Facts about Prudhoe Bay, Alaska.” The Wilderness Society, 2012, www.wilderness.org/articles/blog/7-ugly-facts-about-prudhoe-bay-alaska.

- “BP to Pay out $25m for 200,000-Gallon Alaska Oil Spill in 2006.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 4 May 2011, www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/may/04/bp-25m-north-slope-oil-spill.

- “Bioaccumulation.” Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bioaccumulation.

- “Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.” Alaska Conservation Foundation, https://alaskaconservation.org/protecting-alaska/priorities/protecting-lands-waters/arctic/anwr/.

- “Imperiled Polar Bears Face New Threat in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.” WWF, World Wildlife Fund, www.worldwildlife.org/stories/imperiled-polar-bears-face-new-threat-in-alaska-s-arctic-national-wildlife-refuge.

- Comay, Laura B., et al. Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR): An Overview. 2018, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL33872.pdf.

- “Caribou People.” Gwich’in Steering Committee, 16 Nov. 2012, https://ourarcticrefuge.org/about-the-gwichin/caribou-people/.

- Harball, Elizabeth, and Nat Herz. “As Oil Drilling Nears In Arctic Refuge, 2 Alaska Villages See Different Futures.” NPR, NPR, 3 July 2019, www.npr.org/2019/07/03/738145007/as-oil-drilling-nears-in-arctic-refuge-2-alaska-villages-see-different-futures.

- Wallace, Scott. “ANWR: The Great Divide.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 Oct. 2005, www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/anwr-the-great-divide-69848411/.

- Arctic Change – Land: Permafrost, www.pmel.noaa.gov/arctic-zone/detect/land-permafrost.shtml.

- Schmitz, Oswald . “Why Drilling the Arctic Refuge Will Release a Double Dose of Carbon.” Yale E360, 2021, https://e360.yale.edu/features/why-drilling-the-arctic-refuge-will-release-a-double-dose-of-carbon.

Turetsky, Merritt R., et al. “Permafrost Collapse Is Accelerating Carbon Release.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 30 Apr. 2019, www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01313-4.