“Freedom is not free, and we are very grateful for your leadership,” expressed District 47 State House Representative Anna Eskamani. On July 21, 2022 at the Alfond Inn in Winter Park, FL, the Representative presided over a lunch roundtable discussion between local Central Florida lawmakers, community stakeholders, and the U.S. Global Leadership Coalition. The topic: the intersection of the climate crisis and United States national security.

This talk was guided by former marine aviator and active diplomat General John Castellaw, who also happens to be a farmer: a family trade for generations. An older military man and a farmer from—as he described it, “Redlandia Tennessee”—who believes in climate change? Moreover, who sees the military as key to stabilizing our ecosystems? A heartening thing to behold.

What is the USGLC?

The USGLC is a “broad-based influential network of 500 businesses and NGOs; national security and foreign policy experts; and business, faith-based, academic, military, and community leaders in all 50 states who support strategic investments to elevate development and diplomacy alongside defense in order to build a better, safer world.”

What the organization looks like in practice is – 18 bipartisan former cabinet secretaries, 500 businesses and NGOs, 250+ retired three and four-start generals and admirals, 3k state leaders, and 30k veterans for smart power. These members are then deployed in the capital and around the country to push for security and prosperity, at home and abroad.

Photo credit: USGLC

Photo credit: Unsplash

How is the U.S. International Affairs Budget connected to climate?

International Affairs is the art of maintaining positive relations among the global community- an important goal, to be sure. However, only 1% of the U.S. federal budget goes to international affairs, a figure which may be surprising. An overarching goal of USGLC in its work building relationships and bipartisan support is to make the case for expanding the IA Budget.

In order to ensure security and prosperity among nations, this diplomatic craft cannot ignore the looming climate crisis, and the destabilizing effect of extreme weather and natural disasters on industry and agriculture. Those of which are the two pillars of livelihood among all nations.

Prosperity over the longterm means enacting measures to fend off the worst effects of climate change on communities and countries at large. These measures might be best summarized by the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs, which IDEAS For Us advances through our global eco-action projects.

Diplomacy, Our Great Climate Tool

Of course, the word military denotes war and combat. What gets understandably lost of this concept (after all, the U.S. is still stationed in Afghanistan) is the role of the military in actively building peace (a lá the United Nations SDG #16). Perhaps military, in this era which requires extreme cooperation and mutual aid among nations, is a misnomer. The job itself is peacekeeping—the worse case scenario is the fight.

A veteran with 36 years of experience serving the U.S. Marines, General John Castellaw saw his fair share of combat. However, he stresses the lessons about peace he learned both from active combat and from more delicate missions to aid civilians, and how we might apply them to the climate threat. The following article recounts the roundtable exchange between Central Florida environmentalists, community stakeholders, and General Castellaw’s thoughts on why climate change is a military issue. They approach this topic from a humanitarian as well as an economic standpoint.

Photo credit: Unsplash

1. Climate change causes mass migrations

Castellaw begins the discussion overseas, in the tenuous climate of Africa. David Beasley, head of the United Nations World Food Program, said “We have a ring of fire circling the earth now from the Sahel to South Sudan to Yemen, to Afghanistan, all the way around to Haiti and Central America.” This ring is fueled by climate change, the pandemic, and existing conflicts. All of these factors contribute to the more than 178 million people who are at risk of starvation, should things continue in their current manner.

Castellaw states that United States should of course be interested in these alarming statistics from a humanitarian standpoint. Moreover, he considers that knowing we are implicated economically in this mess might invoke more listening ears in the U.S. As this food and climate insecurity inevitably leads to mass displacement and migration, the country is increasingly involved in the drama, and its security is progressively threatened. In our interconnected world, the Ring of Fire burns from content to continent.

Photo Credit: Union of Concerned Scientists

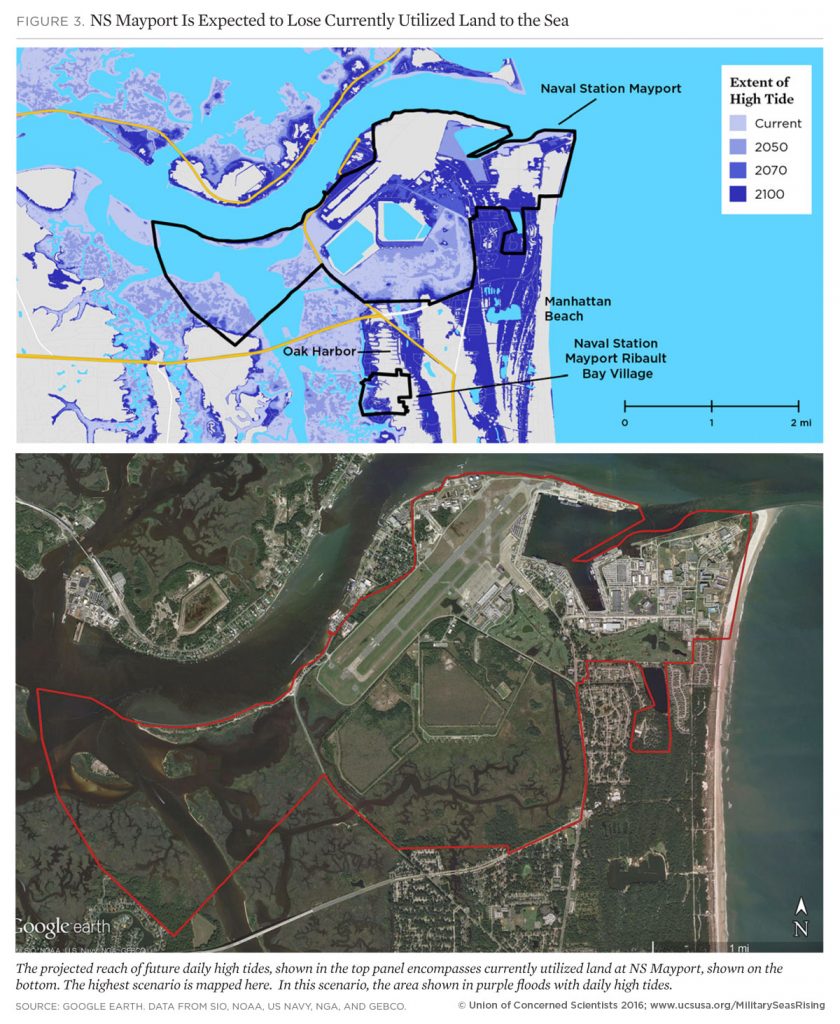

2. Military bases in the US are under "climate siege"

How is climate change directly affecting the military’s operations?

Castellaw describes how Mayport military base in Jacksonville, FL is threatened by rising sea levels. Many of the roads leading into Mayport are flooding. The St. John’s River running through Jacksonville is subject to increasingly severe surge storms. “This military infrastructure, into which the US has poured billions of dollars, is at risk,” warns the general.

Climate change-induced, extreme weather does not only threaten Florida. The issue is in fact pervasive to the whole eastern coast of the U.S. Military headquarters in South Carolina are affected. Notably, the Marine base on Parris Island is routinely evacuated due to the dangers of flooding. The water threatens to cut off the causeway into Norfolk, the “crown jewel” in the Navy’s system of bases.

All military operations are affected:

Beyond the Marines and the Navy, Castellaw reminds us that the Air Force’s operations are also imperiled. Climate-related floods have destroyed infrastructure at Offutt Air Base in Nebraska. Not only is this damage incredibly expensive to the U.S. military and citizens’ tax dollars, it also interrupts the work the military does. As extreme weather events directly impact military bases, the connection between sustainability and the U.S. protective forces begins to spell itself out.

Photo credit: Unsplash

3. As the seas are rising, the military’s recruitment pool is shrinking

In terms of longterm sustainability as an institution, how does the U.S. military currently fare? For years, Castellaw illustrates, the military had a 70% approval rating among U.S. households. In the last 3 years, that number has plummeted to 45%. The general laments that only 15% of parents of those that are 17-24 year-olds have a relationship to someone who has served. This number is significant, notes Castellaw, “because parents are the single most important factor in military recruitment.”

There are 331 million+ people in the United States. When one sifts down to the military recruitment “sweet spot” (17-24 year-olds) and weeds out those with civil convictions against joining the armed forces, that number appears to dwindle to 450,000, regrets Castellaw. This small recruitment pool, combined with a major decline in confidence in the military, does not bode well for the institution’s survival.

If the military hopes to counteract this threat, the general hypothesizes, it must take seriously the role that climate change has in aggravating conflicts overseas and in impacting domestic military facilities. “The greatest treasure we have in the United States and the one that we should be last spent is the blood of the men and women who serve.”

Perhaps if the military were to takes a more aggressive stance on mitigating climate change and its negative effects, it can instill the confidence in U.S. citizens it needs for survival. By preventing the erosion of U.S. national security caused by climate change, the military may gain the trust of a climate-anxious generation.

Photo credit: Unsplash

4. The military can stabilize governments by stabilizing climate

How can U.S. diplomats aid the developing world in the fight against climate change and its effects? Castellaw recounts his time in the Horn of Africa, also known as the Somali Peninsula, working to stabilize communities against insurgents. The general recalls a particularly effective task force in Djibuti, which consisted of a well-drilling and veterinarian crew. Why would such a seemingly ad-lib team be such productive peace-builders?

The general explained the long-lasting drought in the area, and the great economic hardship it caused the residents. Their economy is based on goats and the arduous work of women, who walked miles for water. As a result, the vets began to vaccinate the goats against diseases, building their economic value and thus increasing confidence of residents in the U.S.-backed government. Subsequently, the water crew drilled a well near the village so the women wouldn’t have to walk so far. Thus, the women’s quality of life increased, and so did their ability to provide for their families. “When mama’s happy, everyone’s happy,” quips Castellaw.

By aiding this African country in its sustainable development, the diplomatic crew decreased the opportunity for insurgents to gain traction. All the while, they supported the existing government without violent combat. According to Castellaw, it is imperative to build peoples’ economic well-being. Such diplomatic missions go a long way in building durable peace.

Photo credit: Unsplash

6. The military can lead the way in sustainable development at home and abroad

If the U.S. is to be a global leader in the climate space and reach clean energy solutions, jobs for this green future are a necessity. How can the U.S. work with its allies to make sure it is leading in this space, and that its allies are coming along, as well? Also, how should the U.S. deal with other countries that are not taking on this work?

Castellaw notes the need first for internal agreement. “Senator Graham said, ‘Hey, why should we focus on green jobs when China’s not doing it?’ Why we should do it is first because it’s the right thing to do and second, because the U.S. is still the world leader.” Even in darker days, notes Castellaw, the U.S. is still respected for its ability to carry out incredible projects.

General Castellaw doesn’t shy away from the perhaps anti-climactic roadblock to sustainable development: “A lot of my generation doesn’t want to change.” The general recalls a bit of family history to illustrate his point, recounting his family’s difficult transition to new work with the advent of superior farming equipment in the 1930s. “We need to to do a better job of planning that transition for people. We need to fill holes like electrical infrastructure for charging cars. We need to do those things that move us to the front of the pack in transitioning to a cleaner world.”

Castellaw is sure to recognize the victories the military currently holds: employing more fuel-efficient vehicles, flying smarter, and replacing fossil fuels with solar panels and wind generators in some areas. “We’re doing this, we’re just not doing it fast enough. We need to get the old dogs out of the way so that new minds can lead the pack.”

Photo credit: Unsplash

6. How can we change minds and create unity against climate change?

What should we say to our friends or family who are veterans, and who don’t believe in climate change?

In order to answer the question, Castellaw draws on his experiences with other farmers in Tennessee. “I was sitting at a table with a group of farmers at a co-op, and the farmer sitting next to me said, ‘Hey I’m tired of this climate stuff. It’s just like it always has been.’ Another fellow at the co-op retorted, ‘What are you talking about? You know the growing season for cotton has lengthened by two weeks. You know we’re having to create new corn seed for this weather.” Corn likes warm days and cool nights, Castellaw explains, but sometimes now at night it doesn’t get below 80 degrees in Tennessee. On these peculiar hardships, most farmers can agree.

Therefore, the general recommends a fact-based response, but filtered through the “speaking code” of the community. Among many farmers in Tennessee, he says, the word “climate” is verboten. You have to know who your audience is, and “pitch” to them. Everyone can see what’s going on, but it’s how you converse about it that allows you to reach people or alienates them. “Sometimes,” the general jokes, “You just have to pull a P.T. Barnum over in Tennessee.”

One final, hopeful thought

When we go and talk to our communities about why climate change matters from a national security perspective, how do we make the case for investing in climate solutions and enacting them as soon as possible?

General Castellaw says it comes down to this: “If we don’t act, if we don’t take charge, if we don’t exert ourselves, then what we do is put young, American men and women at risk. They will have to be put into the breach because we’ve failed. If we want to conserve the blood of those soldiers, then this is something we have to do. And it’s hard. But we have to do it.”

Why have hope? Sitting in a room with veterans across the age spectrum and hearing them not only validate climate change as a dire issue, but also call for immediate action by the U.S. military to counter these catastrophes, is invigorating. It’s a reminder that every generation struggles both existentially and in building productive partnerships to accomplish their dire goals.